by Kevin Hagan

Those of us involved with talking about writing and helping others find their expressive voices often spend a lot of time in conversations about the writing process: pre-search→ brainstorm→ research→ draft→ write→ revise→ rewrite→ edit→ submit. However, we tend to pay very little attention to one very important aspect: the actual mechanics we use during the stages of the writing process.

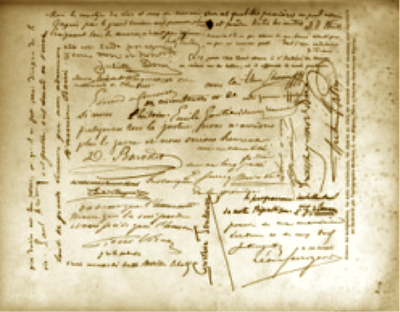

Mechanical processes are the methods we use to get the words from our heads to a medium of distribution. Writers use a variety of mixed processes to produce their work. Stephen King does his writing on a vintage manual typewriter. George R.R. Martin writes on an 80s era DOS-based word processor. Elin Hilderbrand, “Queen of the Summer Novel,” writes on a yellow legal pad and transfers it to a computer for her first edit, and James Joyce often wrote on cardboard with a crayon.

Many modern writers who have a choice of creative media still choose pen and paper for their first drafts. These habits may seem quirky, but they are actually supported by science (well, maybe not the crayon on cardboard thing, but certainly the technique of writing by hand). Brainstorming, drafting, and writing all benefit from the manual act of physically getting words on a piece of paper, and it begins with brainstorming.

Brainstorming is a purely creative process. The kind of linear imagery offered by the computer-generated text doesn’t facilitate creativity the way the less straightforward brainstorming techniques can. Likewise, drafting employs much of the creative process, only a bit more directed by logic. Drafting is the step in the process that attempts to logically order the connections and correlations you discovered in brainstorming.

Brainstorming is a purely creative process. The kind of linear imagery offered by the computer-generated text doesn’t facilitate creativity the way the less straightforward brainstorming techniques can. Likewise, drafting employs much of the creative process, only a bit more directed by logic. Drafting is the step in the process that attempts to logically order the connections and correlations you discovered in brainstorming.

Manually writing a draft forces the brain to slow down to match the speed of a writing hand. The brain reads and responds to each word and each sentence as it’s being written, revising and creating flow for the next sentence to come. Research shows manual writing increases cognitive function and allows the super powerful cortex of the subconscious to apply itself. Much of the same thing happens when we doodle or take handwritten notes during lectures. The mind simply processes both incoming and outgoing information better when we write by hand.

Many people lament the slow, laborious process of transferring thought to paper and from paper to computer. However, if you just consider these to be a part of your process, it can become second nature. Like anything else, it just takes practice. Focusing on that process instead of on a finished product might seem either wasteful or decadent, depending on your personal tastes, but is actually instrumental in producing your highest quality work. The University Writing Center is a great place to go build or fine tune your own process and get the kind of encouragement and advice that will keep both your linear and creative sides working together—even if we have to pull out the crayons.

Many people lament the slow, laborious process of transferring thought to paper and from paper to computer. However, if you just consider these to be a part of your process, it can become second nature. Like anything else, it just takes practice. Focusing on that process instead of on a finished product might seem either wasteful or decadent, depending on your personal tastes, but is actually instrumental in producing your highest quality work. The University Writing Center is a great place to go build or fine tune your own process and get the kind of encouragement and advice that will keep both your linear and creative sides working together—even if we have to pull out the crayons.

References

Flowers, L. and Hayes, J. (1981, December). A cognitive process theory of writing. Cross-Talk in Comp Theory: A Reader. (3rd ed. pp. 253-277). Urbana, Ill: National Council of Teachers of English.

Hensher, P. (2012). The missing ink: The lost art of handwriting (and why it still matters). London: Macmillan.

May, Cindi. (2014, June). A learning secret: Don’t take notes with a laptop. Scientific American. Retrieved from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-learning-secret-don-t-take-notes-with-a-laptop/

Richards, T. L., Berninger, V. W., Stock, P., Altemeier, L., Trivedi, P., & Maravilla, K. (January 01, 2009). Functional magnetic resonance imaging sequential-finger movement activation differentiating good and poor writers. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 31, 8, 967-83. Retrieved from http://0-search.ebscohost.com.wncln.wncln.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=44620513&site=ehost-live